The other day, I was walking around Austin and saw the mailman driving his white midget truck around town. After watching him hop from mailbox to mailbox, I realized that he’s the perfect example for studying how electricity and the Internet have changed human consciousness.

Email basically steals his job, but how?

Before the telegraph and any kind of electric technology like iPhones, sending words was the same thing as sending a package. Communication time was synonymous with transportation time. If I wanted to go eat pineapple pizza with my friend on Friday night, I couldn’t just text him on Wednesday. I would have to send a message many days in advance by writing him a letter. Then, after I dropped off my letter at the Post Office, an actual human would take it to my friend by the hoofs of a horse.1

As Marshall McLuhan wrote in his seminal 1964 book Understanding Media:

“It was not until the advent of the telegraph that messages could travel faster than a messenger. Before this, roads and the written word were closely interrelated. It is only since the telegraph that information has detached itself from such solid commodities as stone and papyrus, much as money had earlier detached itself from hides, bullion, and metals, and has ended as paper. The term 'communication' has had an extensive use in connection with roads and bridges, sea routes, rivers, and canals, even before it became transformed into 'information movement' in the electric age.”

In-person messengers also meant that all messages took a long time to arrive. The most fascinating example of this is the Declaration of Independence. After it was signed in Pennsylvania on July 4, 1776, it took 16 days for the news to reach Virginia. Traffic wasn’t a bitch; slow was just how things were. People had to wait their turn. Plus, if road conditions were sus for the horses with puddles and mud, the mail could’ve taken even longer to move.

As McLuhan pointed out, in the electric age, information moves via electricity, transcending time and space. Before email, many messages were delivered by some dude who drove an automobile and walked up to people’s front porches. That guy’s day involved waking up, putting on his pants, brewing a morning espresso, driving his normal car to the post office, and circulating every cul-de-sac in his mail truck. The word “mail” comes from the Old French male, which means “bag.” The messenger used to carry all of our messages. Communication was a team sport, just like a quarterback handing the football to the running back.

But now, email not only removes the need for a human messenger, but also all of the other technologies that enabled the delivery of mail. If mail no longer needs a human, then it also doesn’t need a car or a road. When I send an email, I don’t give a shit if the roads are icy or if the mailman is snoring. All I need now is an Internet connection to connect with everyone all at once, 24/7.2

In physics, speed equals distance divided by time. But as this short study of the mail shows us, this equation is irrelevant in the age of the Internet because communication is as automatic as breathing. Marshall McLuhan called the Internet the “global village” decades before it existed. In his eyes, emails and any kind of instant message represent the simulation of human consciousness that brings us back to what life was like in an oral society. In a world without writing, there was no such thing as individualism and privacy to read a book; the message and the messenger were the same thing because all people did was talk to each other in their tribes.

Every time I see the mail truck, I often think about the things I just wrote. I wonder if the mailman will even exist in the future. I wonder when it will be the last time that I see one of those compact white cars. But whether any of this comes true or not, I’m more worried about the eradication of postcards and letters and everything imperfect and human and analog that evaporates in the eternal rush to efficiently go nowhere.

Links to This Essay

Content-Life Balance

I’m worried that the lives of writers and content creators like myself have been invisibly infected by an incessant pressure to post online. I’m worried that keeping people in the loop with my next intellectual poop skews some sacred part of my own personal development.

iCloud Stole My Memories

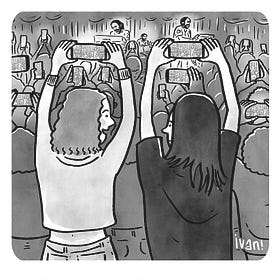

“I often worry that our generation is so consumed with capturing every waking moment that we miss out on every waking moment.”

Notes

Since there wasn't as much back and forth, people also had to be very clear with when and where they were meeting up. This translates well to the texting world, where I've found it useful to text people days in advance about setting up dinners, walks, and workouts. School never really teaches you that you have to be proactive in maintaining friendships since the ritual of a regular recess hour doesn’t exist—unless you create it.

Before the telephone, there used to be business hours for communicating with people who lived outside of our homes. Even the mailman only comes during the daytime. Given this, I'm a big believer in strict "business hours" for technology. In other words, parts of my day and entire nights will be on Airplane Mode or Do Not Disturb.

My friend and I tried sending just handwritten lettes to each other to see what it was like.

We did that for half a year and it was interesting. Because of the delay, we had to make sure to our ideas and writing clear the first time or else you'd waste weeks for clarification.

I enjoyed reading this Baxter! I wrote about the history of communication between early Canada and Europe, and it was even worse than what you describe. They couldn’t send letters for a huge chunk of the year because of the ice blocking boats! It made me appreciate just how much we’ve reduced the delay in communicating.