Last week at the gym, I heard someone say: “All that matters is how you use new technology.” In the past, I would have agreed with him. But now, after studying the work of Marshall McLuhan, I’m not so sure that I do.

In case you haven’t heard of him before, McLuhan was the father of media studies. In 1964, he wrote the seminal book Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, which explored how technology shapes human consciousness and culture. One of his most enduring and provocative ideas was that the medium is the message.

As he once wrote:

“Societies have always been shaped more by the nature of the media by which men communicate than by the content of the communication.”

For example, if you want to study the effects of TikTok, focus on how short-form video affects our senses rather than the video content itself. Whether you see a quick quote from Huberman or a half-naked girl rubbing ketchup on her skin, TikTok changes your perception, whether you realize it or not.

I don’t know how many times I’ve heard people say something like, “I still use TikTok, but I’m just careful with the content I’m consuming.” I’ve always felt like something was off about that statement. I used to convince myself I was “learning” on Instagram Reels or YouTube videos, but some part of me knew that this entertainment was numbing and couldn’t truly be educational. Videos didn’t fill me up the way books did. Like Cheez-Its, they were snacks that never quite quenched my thirst for knowledge.

The Electric Light

McLuhan once wrote that content “is like the juicy piece of meat carried by the burglar to distract the watchdog of the mind.” It’s a distraction from what’s really going on.

In other words, technology is not neutral. It will still subliminally shape our senses no matter how we use it. Every medium has an intrinsic nature to it that works some sensory muscles and atrophies others. TikTok is TikTok. TV is TV. Writing is writing. Crucially, he’s not saying that content doesn’t matter, but that it plays a subordinate role in studying the true effects of technology.

To see this, McLuhan asks us to think about the effects of the invention of the electric light bulb on society. Football and baseball games can go on at night. You can drive your car when it’s dark out. You can work past sunset. You can see the crispy chicken parm on your plate at a restaurant. You can read a book in the warm embrace of your bed before you fall asleep, instead of having to hover over a precious candle.

There is no content in the electric lightbulb, but it changed the entire structure of our society. The medium is the message.

Wolves

McLuhan also wrote that technologies are extensions of our bodies. A car is an extension of the foot. A book is an extension of the eye. A podcast is an extension of the ear. When a new tool comes along, it disrupts all of our senses. Sure, all of the senses are individual, but they coexist in an equilibrium. To impact one sense is to impact all the senses.

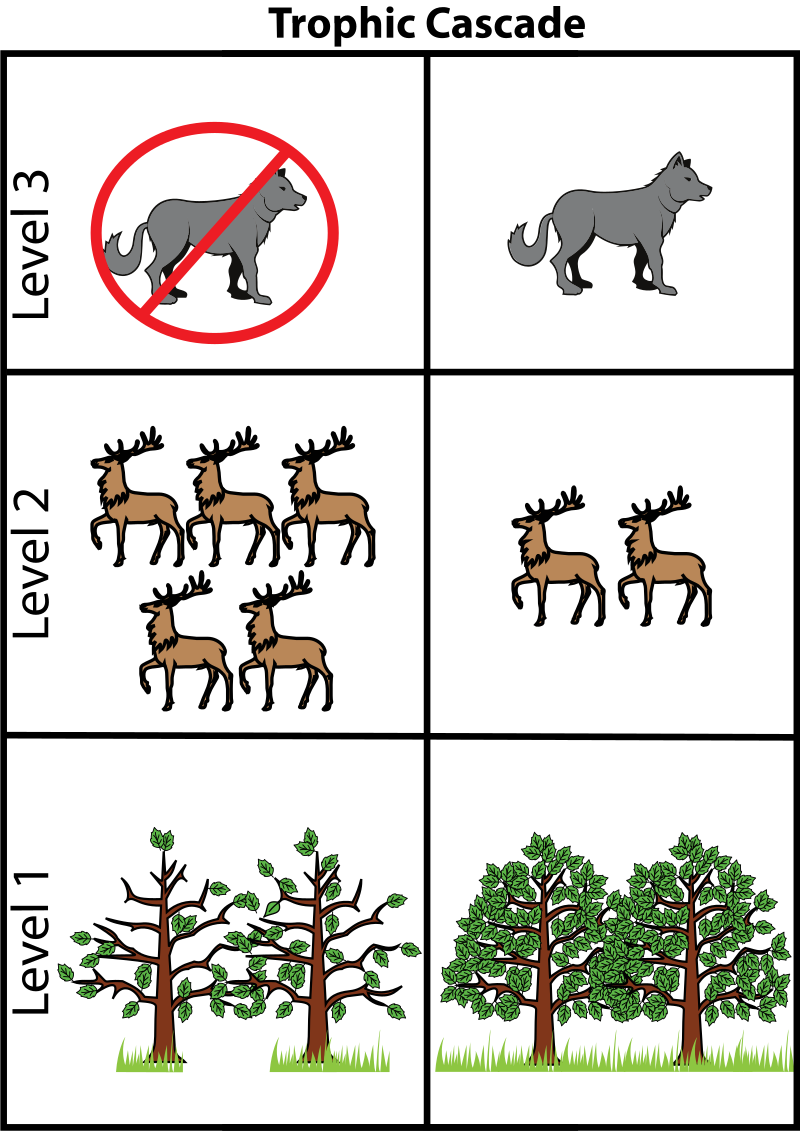

This means that technology isn’t just a tool—it’s an environment. The way I like to think about this is like an ecosystem. In biology, there’s a concept called a trophic cascade, where a change at the top of the food chain spirals down to lower levels, changing the entire structure of nature.

For example, in the early 20th century, scientists had no idea that the extermination of gray wolves would harm Yellowstone National Park. At the time, they thought that all ecosystems were built from the bottom up. If you watered the plants and picked up all the granola bar wrappers, then the environment would thrive, from caterpillars and deer all the way up to grizzly bears.

But in 1995, after wolves were brought back after a 70-year absence, biologists saw that top-down effects also mattered. Without apex predators like wolves, elk overpopulated the park. Too much elk meant too much grazing on grass and trees, robbing birds of homes and beavers of materials to build dams with.

Just like the butterfly effect, the impact of the wolves trickled down everywhere else in the ecosystem—all the way to the level of plants themselves. It’s not an exaggeration to say that wolves change rivers. In the same environmental way, any new technology disrupts the sensory equilibrium, which changes everything else.

Books vs. Podcasts

I’ve also found it helpful to think about this through the lens of reading a book versus listening to a podcast. Imagine that you could listen to the Odyssey or you could read it. Even though the content is the same, you will have two dramatically different learning experiences.

I don’t know about you, but there are hundreds of podcasts I’ve listened to where I can’t remember a single thing that I’ve learned. That’s terrifying. Sure, some podcasts actually hit different and stick, but it’s way more rare than with books. In this sense, listening to podcasts is like filling up a bucket with holes in it. The information just leaks out.

But when I’m reading a paragraph, I often stop to ponder its meaning. With my 0.38 mm black Pilot pen, I write notes in the margins, battling with the writer. I underline powerful passages. I circle delicious phrases. Unless I’m reading fiction, I’m always asking myself, “Is this true?”

A podcast is just not the same. A podcast implies passive, background listening. The message of a podcast is multitasking, but reading demands all of you at once. Its message is focus and presence. Reading is grappling. It’s intellectual strength training. It’s intimacy. It’s the medium for truth. And these two different ways of interacting with information change people.

I’m not saying I won’t listen to podcasts or audiobooks ever again or that you should do the same. They have their place, and I love listening to them while driving. But when it comes to learning, listening to a podcast is like going to the sauna and calling it cardio—it’s a shortcut. If all you do is learn via podcasts and you have eyes to see, then there’s a decent chance you are blind and are being deceived.

Milk

More than anything else, to me, the “medium is the message” means that the idea of the “information diet” may not be as important as the way you consume information.

Sure, Jordan Peterson might have some epic lectures on The Bible, but what scares me is when people watch those lectures and never go to war with the Great Books on their own. Without the medium of writing, people stop thinking for themselves because they don’t know how to think for themselves. It’s no coincidence that the smartest people in the world—the deepest thinkers—are all readers.

When a baby boy needs milk from his mom, what happens if he never sucks on the teat? What happens if mom decides to swap out her own breast milk for a liquid that has the exact same nutritional content as the real milk? As I’ve learned from my airway dentist, a lot changes. The medium is the message.

Thank you to

, , and for inspiring this essay. Oh, yeah, and, of course, Mr. Marshall McLuhan. Understanding Media is by far the greatest book I’ve read, and you have to read it.

Great writing, made me think through some of the pieces. Awesome job!

Fire